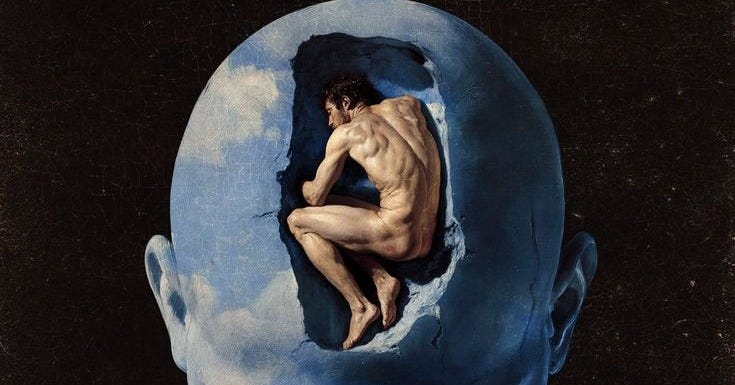

Mindless Part I

A man discovers his late father's journal, revealing a harrowing family secret that challenges the very essence of humanity.

Schafer's Quill is your weekly escape into the realms of fantasy, science fiction, horror, and more. Subscribe now to explore captivating stories delivered straight to your inbox—adventure is nigh!

Remembrances

“Do you think all things have a physical explanation?”

Dad was a frail man. His body was so thin that all his clothes seemed baggy on him, no matter the size. His watch dangled loosely on his wrist, and his oversized glasses appeared even larger on his gaunt face.

He sat forward in his chair, arms braced on his knees, holding a bottle of beer as he watched my younger brother, Tyler, chase our pet dog with all the coordination you’d expect from a four-year-old.

“What?”

He took another sip of beer, sighed, then reclined. “I’m asking if you think the physical world is all there is—or if maybe there are some things that exist beyond it.”

“Like?”

He glanced at me. Even behind those thick lenses, I could see the weakness in his eyes, something not even his warm smile could hide. He tapped the side of his head. “The mind.” He looked back at Tyler. “Truth is, I don’t think so… most of my peers don’t. The mind, the consciousness—it's all explained by the physical wiring of the brain. Just… a bunch of molecules shooting electrons at each other. We just don’t know how.”

I had heard about this before, at school. Some of my friends had watched a TED Talk on the mind-body problem and suddenly considered themselves expert philosophers on the workings of human consciousness. I didn’t care much for it, but it was no secret that Dad was a neuroscientist. That meant they always found a way to drag me into the conversation.

“How can dead things make living things?” I repeated a question I’d heard from them aloud.

He glanced at me again and grinned faintly before returning his gaze to Tyler. “That’s the question. Except it isn’t, though, is it?”

A cool evening breeze blew through, cutting through my shirt and making me shiver. “It’s not?”

“Nope. That question isn’t a big mystery. A living thing is just… a thing, like anything else. A collection of matter, reacting to other matter. How non-living things can make living things is no different from how non-starry things can make stars.” He paused for a moment. “No, the question isn’t how living things came about—it’s how those things woke up. That’s what we don’t understand. How non-thinking things can create thinking beings that know they’re thinking. Is it just… a result of all the other processes? If you remove those, will all that… awareness vanish, or is there more to it?”

I gaped at him for a moment, then went back to scribbling in my sketchbook. “Dad, I’m twelve. I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

He chuckled. “A clever enough twelve-year-old to be facetious about it.” He mussed my hair.

I looked up at him again. His eyes were still trained on Tyler, who had noticed him staring and now offered a wide, toothy grin and two waving arms.

“Hi, Daddy!”

He waved back, but the moment Tyler looked away, something else settled on his face. Something somber.

“What would you say about someone who didn’t have a mind?” he finally asked softly.

“I… you mean brain dead?”

He shook his head. “No. The brain’s alive. The body’s alive. But there’s no mind.”

“I…” I tried to wrap my head around it. How could something like that even happen? I frowned and shook my head. I had no idea what a person like that would be—but I knew what they certainly weren’t. “I’d say they’re not human.”

His head whipped around, and I drew back. He looked at me, his lips quivering, but he pressed them together, swallowed, and steadied himself with a deep breath. “You might be right,” he said softly but with strain.

Tyler ran up the porch steps on all fours and plopped himself down on the other side of Dad’s chair.

“Daddy, look!” He held up his small hands, offering one of those rocks that almost seemed like a crystal. The kind that fooled younger kids into thinking they were valuable, though they were practically worthless.

Dad mocked amazement, and Tyler beamed before holding the rock an inch from his eye. That sadness returned to Dad’s face.

“Dad?” I called. “Why are you asking all that?”

Tyler yawned, and Dad picked him up, setting him on his lap and cradling his head to his chest. “I don’t know, son. I don’t know much of anything anymore. Except…”

He said the next words so softly I doubted he thought I heard him—and I pretended not to.

But I did.

“I’ve done something terrible.”

The brakes of my car whined as I pulled into the driveway of our old house.

“Wow.” Tyler gaped at the porch from the passenger seat. “It’s been a while, huh?”

“Yeah,” I said absently, as an old memory slowly faded into the mist of my unconscious. It left me wistful, wondering why it had surfaced in the first place. I stiffened slightly when Tyler clapped my shoulder, squeezing it tenderly. I grasped his hand, looked at him, and he offered an emphatic smile—the kind that said, It’s alright. It hurts, but it’s alright.

I wasn’t sure I could speak without my voice breaking, so I simply nodded and swallowed the knot in my throat before opening the door and stepping out.

The brittle grass, patched with brown and yellow, crunched beneath my feet. Nothing like the soft green from that memory… or any memory of my childhood. Tyler stood beside me, his hands tucked into the pockets of his brown jacket, gazing at the lawn. He almost mirrored my posture, and I guessed the same thoughts were creeping through his head.

He wasn’t that four-year-old running around clumsily anymore. We were about the same height now, though Tyler was clearly the better-built one. I had taken after my father—frail frame, and eyesight to match.

“We should have visited more,” I muttered.

“Shoulda, coulda, woulda.” He smiled at me, then jerked his head toward the house. “Come on.”

Our feet clopped on the wooden planks of the porch, and the door, its paint peeling, creaked as Tyler opened it. I stepped in slowly.

Memory is a funny thing. It’s rarely true to reality given enough time, but it’s the only reality we have. My memories had time to get things wrong, so the house as it was clashed with the home I remembered, creating a present that was both alien and familiar—a shadow of what it had been.

At least I remembered that it had never been so dead. That’s all it seemed like to me now: a dead place. The air was still, dust particles suspended, lit for fleeting moments by sunlight streaming through the windows. It smelled like death too. Or death pending—the smell of the elderly.

I could imagine Dad hobbling through the halls, hunched over his walking stick. The thought made my chest ache. I should have been here more. Been with him. Maybe he wouldn’t have—

Tyler stepped ahead of me, strolling into the living room. “It’s the same chair,” he said, running his finger over the arm. “He’d sit here, watching some show. We’d be on the couch, doing whatever we were doing.”

I chuckled softly. “Yeah… hey… let’s get to it.”

He nodded. “Yeah.”

We went back to the car and returned with boxes, ready to clear away the things that didn’t need to be there anymore. Dad’s things. We left the rest—the pictures of the four of us: Tyler, me, Dad, and Mom. Those were rare. That period, when we were a whole family, was short.

I went upstairs and couldn’t resist stepping into my childhood room. I took a deep breath. It was exactly how I’d left it. Nothing had been moved. I set the box down and strolled inside. Every sight was a trip into the past.

I knelt by my bed and pulled out my toy chest. The first thing I saw was a model plane, its surface covered in glue.

I still remembered the day it broke. I had saved my allowance for weeks to afford it, and it took me days to finish assembling. It was my prized artifact. Until Tyler got his hands on it.

“No!” I cried when I saw Tyler on the ground, trying to stuff the wing back on and making it worse. I ran up and yanked it away. “What did you do!” Tears were already flowing down my cheeks, and anger seethed up from my chest, into my throat, nearly choking me.

“I-it was an accident!” he stammered. “I just wanted to play with it!”

“It’s not a toy! I told you that!”

I launched at him, but Dad grabbed me from behind.

“What’s wrong?”

“I was just playing with the plane, then it fell,” Tyler said through sniffs. “It was an accident.”

“He shouldn’t have been playing with it! I told him not to!”

“Hey,” Dad pressed his hand on my chest. “It’s alright. You… gotta be a bit understanding with your brother.”

“Why!” I cried out, red-faced. “You always say that! Every time Tyler does something wrong, you just say he doesn’t know better! That I need to be more understanding! Well, I understand just fine! I understand that he’s just—just a little monster!”

Dad grabbed my shoulder and shook the life out of me, growling so fiercely that spittle flew into my face. “Don’t you ever say that!”

All my fiery rage turned to cold terror. My eyes bulged, and then my lips quivered. A sob burst from my throat.

“Son,” he muttered, but I wrestled myself out of his grip and ran out of the room before the tears came uncontrollably.

I wasn’t sure how long I sat under the tree in our backyard before Dad came and sat beside me.

“It’s not fair,” I said. “He always gets his way.”

Dad put his hand on my back. “I know it seems like that, but… Tyler… he’s a bit different.” His words came slowly, carefully chosen. “He might not learn some things as fast as others, but he will. I promise you he will… and I’m sorry I snapped at you like that. It was wrong.”

I sniffed. “Why did you?”

A slight sound escaped him—a word he decided not to say. “I just… don’t want you calling Tyler a monster, alright? He’s your brother, and he loves you. I know he does.” He swallowed, lingering on the last bit. “And I need you to love him. No matter what, alright? In case no one else can.”

I furrowed my brow. “What do you mean?”

“Will you promise me that you’ll care about him?”

“I… yeah.”

Not long after that, Tyler came down with the plane drowned in glue. His eyes were red and wet, and his words forced through shuddering breaths. “I… I tried to… fix… I’m… sorry.”

I took the plane and hugged him. He’d made it worse, but that wasn’t his intention. That’s what mattered—the thought that went into it.

Dad would’ve said the same thing. Except, when I glanced at him—and he didn’t know I did—he was frowning.

“I remember that.” Tyler squatted beside me.

“Yeah.” He chuckled as he reached for the model plane. I handed it to him, then stood and strolled to the window. That tree was still in the backyard, though the leaves were brown now.

“I think that’s the first time I ever saw Dad snap like that. It scared the shit out of me. I thought he was going to kill you.”

I smiled softly. “Believe me, I was scared shitless too.” I shook my head. “He wouldn’t do that, though.”

“I know. We gonna get back to it?”

I looked at the tree for a moment longer before nodding. We strolled through the house, packing the boxes, and eventually made our way to his study.

“You have the key?”

Tyler handed it to me, and I stepped into the room. A large desk sat across from the door in front of a tall window. The walls were lined with shelves filled with books, and the air carried the scent of an old library.

“He never let us in here,” I said.

I walked the perimeter. “Are we going to pack all these books?”

Tyler shrugged. “Maybe we should just pack the paper for now. Then—” His phone buzzed, and he pulled it out of his pocket. “Hello? Yeah… right. Alright, gotcha.” He glanced at me. “That’s Angie. She needs some help with—”

I waved him off. “That’s alright. I’ll get started here.”

“Thanks, bro. You’re the best.” He stopped at the door. “If I come back late, I’ll bring some take-out. How’s pizza sound?”

“Sounds great.”

He turned to leave but stopped again. “You sure you’ll be alright?”

I nodded and offered a small smile. He lingered for a moment, then stepped through.

“The keys are in the visor!” I called after him.

“Gotcha!”

I wandered around the study for a bit before sitting in Dad’s high-backed, leather swivel chair. I used to sit there when I was younger, pretending to be a successful businessman or a brilliant scientist. He’d always find me. He wouldn’t get mad—he might even let me stay for a while—but it was always clear he’d rather I wasn’t there.

His desk was mostly clean. Tidy. He usually kept it cluttered, except when he knew he’d be leaving for a while.

I leaned back in the chair and pressed a finger between my eyes as a dull ache began to bloom there. “Why?” My voice was ragged.

After a moment, I took a deep breath and began sorting through the papers on the desk. Then I went through the drawers. They were organized, too. I worked through them one by one until I reached the last one. A bit of string stuck out from the corner.

I tugged on it, and the entire bottom shifted. A secret compartment?

Clearing out the drawer, I struggled with the board for a moment before it finally came loose. Beneath it was a single, thin leather book—a journal, really—and the sight of it tickled my memory. I’d seen it before.

I closed my eyes, and bit by bit, the memory came back.

Dad had forgotten to close the study door, and I took full advantage. I’d wandered around, opening books, observing diagrams. Then I found it—the journal.

I hadn’t even managed to open it before Dad stepped in and barreled toward me.

“No!” he gasped, snatching the book away.

I backed off, startled by his sudden outburst.

He took a deep breath, placed the journal back on the desk, then scooped me up. “Hey, let’s go out for some ice cream, hmm?”

He carried me out, locking the door behind him.

I still couldn’t piece together the reason for his reaction, but opening the journal now felt strange. He hadn’t wanted me to see it while he was alive, and I should respect his wishes even though he—

A piece of paper flitted out and landed at my feet.

I set the book down on the desk and picked it up. My name was written on one side. I leaned back in the chair. Was this… a note? That kind of note?

I reached for it with a shaking hand. Whatever was on the paper would be words I’d never heard Dad say, and reading it would mean taking that away.

I took a deep breath and unfolded it.

I’m not a good person. In fact, some would say I’m a terrible person. And I am one of them. I have done things that haunt my every waking moment. They plant questions in my mind like terrible seeds, bearing the fruits of thoughts no father should have. Many of my colleagues have passed already. Whether this is merely a coincidence or part of a grander conspiracy, I don’t know.

As I’m writing this, that blasted journal sits across from me. Even now, I’m not sure why I wrote it—a confession, maybe. Somewhere in my subconscious, I decided I couldn’t bear it alone and sought to offload it, as foolish as that is. I should burn it—the last remnant of my sins, a glimpse into a world that will make you question existence itself. A world I helped create—or rather, a world I helped reveal is possible.

But I can’t burn it. Taking this knowledge to the grave fills me with a fear I’ve never felt before—a fear of what I’ll leave behind.

Tyler, if you’re the one reading this, as pointless as it is for me to say, I love you as much as a father can. And, if you understand, I’m sorry.

And Nathan. If you’re the one reading this, I need you to remember the promise you made me. Love your brother always. He is what he is.

What happens next is up to you. I trust you to make that decision. Whether you burn this book without reading it, read it and tell the world what you’ve learned, or read it and keep the knowledge to yourself, I trust your judgment.

I love you, my sons. And I’m sorry.

I set the paper down and reached for the journal, which suddenly weighed a ton in my hands.

What was he talking about? Knowledge that questioned existence? Conspiracies?

What had Dad gotten himself into?

I stared at the journal, my heart pounding. I took a deep breath.

I almost feared the knowledge.

But I needed to know.

So I turned to the first page.

Journal: John Doe

To me, knowledge was everything—delving into the brain, understanding neural biology. I was a bit of a dreamer, believing that many questions about the human condition could be answered simply by understanding the mechanisms that made us who we are. So when government officials approached me about a project at the bleeding edge of neural research, how could I say no?

I was given access to the lowest levels of a research facility that, to anyone on the outside, looked like a place where scientists stuck wires into rat brains. There was some of that, but far more.

We were a team of twenty—or at least those of us handling the practical experiments. Another team, more theoretical in nature, contributed foundational insights. They were mostly behavioral and cognitive psychologists, I believe, though we didn’t interact with them much.

Our team consisted of ten neuroscientists—including myself—five neurologists, and five neurosurgeons, though the surgeons often operated as a group unto themselves. These were the most brilliant men and women I had ever worked with. Among them, Ivy stood out as the most brilliant of all.

Our introduction was brief, and the mission statement was simple: determine the link between conscious experience and conscious awareness, and explore to what extent they could exist independently of each other.

We were presented with our first subject, John Doe. We never learned his real name. He was a patient suffering from cortical blindness1—not caused by physical damage to the eye, but by a malfunction in the occipital lobe2, specifically the striate cortex3. Our task was to verify his blindness.

John Doe’s testimony was simple and consistent: he couldn’t see. But the tests told a different story.

The first experiment was the hallway test. We placed John Doe at one end of an empty hall and instructed him to walk to the other. He walked in a straight line without issue—our control.

For the second phase, we gave him the same instruction but placed obstacles in his path. Without any additional guidance, he walked the hall, carefully avoiding the obstacles, and reached the other end. When we asked why he hadn’t walked in a straight line, he simply said, “I don’t know.”

Afterward, Ivy spoke to me at length about blindsight4—a phenomenon in patients with cortical blindness where some visual information is processed by the brain, but at a level beneath conscious awareness. It soon became clear we were testing the limits of this phenomenon.

Next, we conducted a forced-choice test. Two sheets of paper were placed on a table in front of John Doe—one printed with vertical lines, the other with horizontal. We instructed him to choose a specific sheet. His choices corresponded with our instructions seventy-five percent of the time.

When asked why he chose the sheet he did, he said he guessed. Yet seventy-five percent accuracy was far beyond what anyone could reasonably expect from blind guesses. This implied that his brain was processing visual information at least on an unconscious level. But if that was true, why did he “guess” wrong twenty-five percent of the time?

“He’s getting in his own way,” Ivy explained. “Think about it—he unconsciously knows the right answer, but he also consciously ‘knows’ he can’t know. So he second-guesses himself.”

“Or his blindsight isn’t entirely accurate,” I countered. “His striate cortex is damaged—maybe it’s partial damage causing dips in perception.” It was certainly the simplest explanation.

“Only one way to find out: more experimentation,” she replied.

Experimentation.

“The only way to test his visual ability,” I said, “is through a forced-choice test. But by your theory, the act of making the choice itself disturbs the results.”

She lit up then. “Ah, but what if he didn’t know he was making the choice?”

“How can someone make a choice without knowing?” Even as I asked, I knew the answer: conditioning.

Her plan was a stroke of genius, so simple that even the psychologists had to bow to it.

We sat John Doe in front of two buttons—red and green. When asked to describe what he saw, his answer was the same: nothing.

The experiment proceeded. The goal was to see how accurately he could select the green button after its position was randomly reoriented following each press—whether green was on the left, red on the right, or vice versa. Crucially, we didn’t tell him to select green.

The buttons were connected to a surround sound system that played an ear-grating noise until he selected the green button. Then the buttons were reoriented, and the test repeated. Simple operant conditioning5. Yet he was entirely unaware of the true nature of his voluntary behavior and its consequences—at least consciously.

This experiment also tested the possibility of unconscious learning.

It didn’t take long before he began consistently selecting the green button. The test ended, then resumed a few days later under identical conditions. Again, he selected the green button without fail from the start.

As Ivy had theorized, the absence of conscious interference allowed the accuracy of his blindsight to reach perfection.

This marked the end of our tests with John Doe. To further examine the limits of this phenomenon, we had to move on to animal testing for ethical reasons.

As I write this, the irony of that statement feels like a spike through my heart.

End of Part 1

Read Part 2

Hi there! Thank you so much for taking the time to read this story.

I’ve decided to split this one into two parts to since I try to keep my posts under 3,000 words (though this one runs closer to 4,000 since I wanted to end on a strong note). This way, the stories are easier to enjoy in a single sitting. Part 2 will be available at the same time next week!

If you enjoyed this part, please consider liking it, sharing it with your friends, and subscribing to Schafer’s Quill so you never miss a story. Already subscribed? Thank you—I truly appreciate your support!

😊

—B. H. Schafer

Cortical blindness - A type of blindness caused by damage to the brain's visual processing areas rather than to the eyes themselves.

Occipital lobe - The part of the brain at the back of the head responsible for processing visual information.

Striate cortex - A specific area within the occipital lobe that plays a crucial role in visual perception.

Blindsight - A phenomenon where people with cortical blindness can respond to visual stimuli without consciously perceiving them.

Operant conditioning - A learning process where behavior is influenced by rewards or punishments.

This is well written. I’m enjoying it.

Great writing—kept me engaged for sure. This kind of subject matter is right up my alley! (I’m a psychiatrist and writer who often blends the two) Looking forward to part 2. Btw, my daughter’s name is Ivy! Kind of a rare one•